I’ve been thinking a lot about high concept pitches lately. Whether or not you’re a writer, you recognize a “high concept” project when you see one: it’s a book or a movie or a TV show that is immediately “gettable” in a line or two, with broad appeal and a unique twist. For example, Mr. & Mrs. Smith is about a married couple who discover they’re both secretly assassins working for rival agencies—with orders to kill each other. You instantly get what the story is about, the main conflict, and what’s more, it’s intriguing—you want to know what happens.

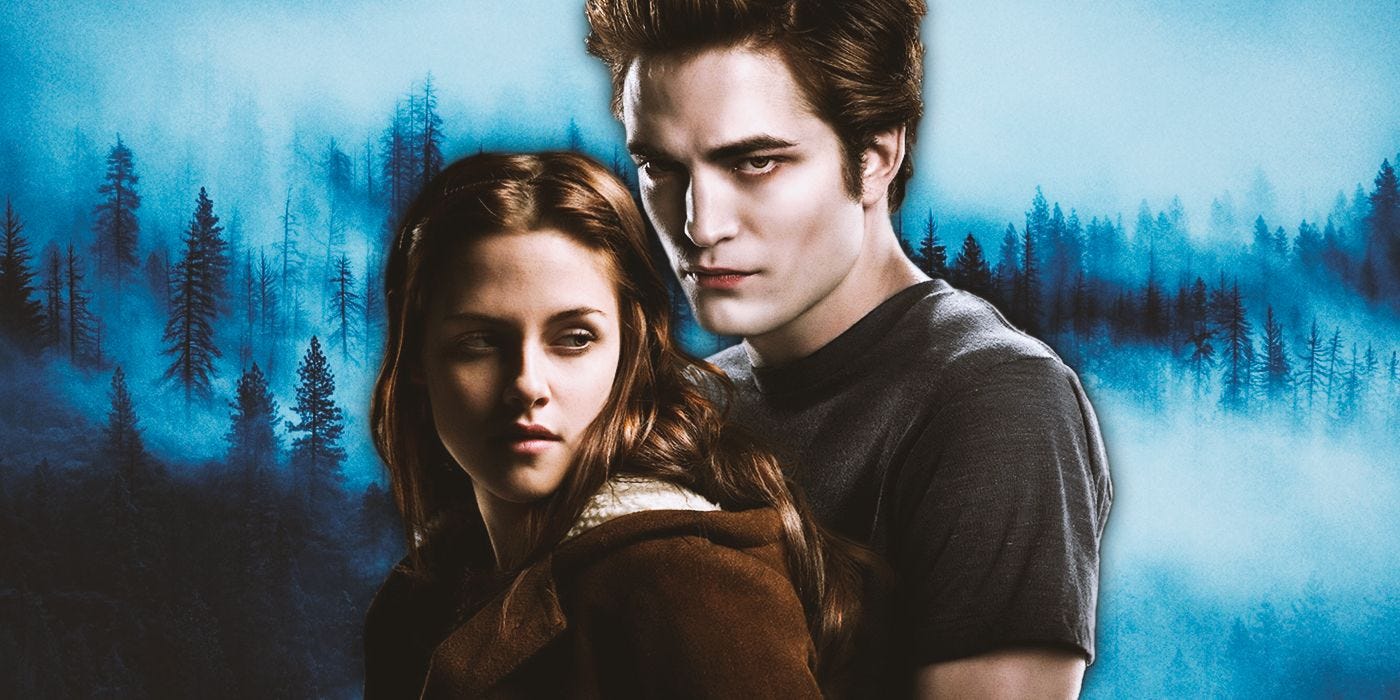

Other examples of high concept ideas would be Jurassic Park (what would happen if you brought dinosaurs back to life?), Twilight (what if a teenage girl fell in love with a vampire?), James by Percival Everett (a reimagining of Huck Finn, but from the perspective of the Jim, the enslaved man), Remarkably Bright Creatures (what if a woman formed an unlikely friendship with an octopus at the aquarium?), and many, many more.

A high concept pitch helps market a project, but I argue that it takes more than a high concept pitch to make a good book, a good movie, etc. When you have authors like Emily Henry or movies like Twilight, there is a secret sauce that makes all the bits and pieces stick together and attract readers and viewers. It’s this secret sauce that makes that high concept work—because who hasn’t gone to see a movie with a great pitch that quite frankly was a waste of money?

Why High Concept Matters

In the publishing world, agents and editors are constantly asking for high concept pitches. Beyond making great stories, they’re easier to sell. As

noted in a recent article about high concept pitches, “If you enter ‘high concept’ as a search term in Manuscript Wishlist, you’ll get forty-eight pages of results.”So far as movies and TV shows go, it’s easy to get buy in from viewers—of course you want to watch a movie where dinosaurs are brought back for a dinosaur-theme-park where everything that can go wrong does! It’s a clear idea that’s easy for a reader or viewer to understand and latch on to. They instantly understand what it’s going to be about.

When I sit down to write a book, one of my first steps is coming up with a high-concept pitch. And when I can’t nail a high-concept pitch for a book, I’ve found that often means I’m missing some important element and will work on it until I get it right (more on this soon including a great resource). For example, there’s a book I’m drafting right now that’s had multiple iterations. I can’t give details just yet 🤫 but none of the pitches were quite right… until I realized that my high concept pitch was missing serious stakes. I figured that part out and suddenly, it came together! My character had BIG stuff to lose if she didn’t fix the situation. It made all the difference.

Selling my most recent novel, Somebody Worth Killing, felt significantly easier than past books (including the two that died on sub)—and it’s probably the highest concept pitch I’ve ever come up with:

An assassin disguised as a PTA president/soccer mom is given the impossible task of killing her own husband, forcing her to choose between the two most important things in her life: her job or her family.

I sent that to my agent, along with an assortment of other pitches, but this was the one we chose to work with—and from there, I expanded it to be a query-length summary, then a synopsis, and finally, the first 20% of the book. We went on to sell this book on proposal because of the high-concept pitch. Selling fiction on proposal isn’t common (unless you’re a big name or it’s an option book)—that’s how powerful a high-concept pitch is. I’m still pinching myself TBH.

The Missing Ingredient: The Fun Factor

This is purely subjective, but when I see a book fail to launch or a movie fall flat at the box office, I often find it lacks something (besides publisher support 🫠)—that it factor that takes what has promise (the high concept) and makes it into a story that people latch onto.

When Twilight came out in 2005, so many people complained about how poorly written it was. But guess what? It has sold 160 million copies worldwide. And not just because it has a high concept pitch:

A teenage girl moves to a small town where she falls for the handsome boy with a secret—he’s a vampire, who’s sworn off human blood—especially hers.

The pitch alone will draw you in, but what makes you stay for the story, despite mediocre writing? What made you buy all four books, signed copies in fact, then watch the movies?? (oh geez, I’m showing my true colors here, aren’t I? but I bet I’m not the only one).

I’ll tell you what made you do that. It’s fun. You can see yourself in these characters—the girl in high school who feels different than everyone else. Falling in love for the first time. The secretive danger so many young people crave.

Likewise, I hear writers complain about Emily Henry—they don’t get why she’s so popular. But I do. It’s not just her good writing or her high concept ideas. It’s because the characters actually have fun on the page. Have you ever watched You’ve Got Mail, that movie from the late ‘90s? Or How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days? Or The Holiday? You know how you can’t help but get sucked in and find yourself smiling through the whole damn thing, even though you know what’s going to happen?

That’s Emily Henry. Her books are fun, full of banter and craveable moments (romantic sigh just thinking of Beach Read, those two enemy-to-lovers authors at adjacent summer cabins, the competition, the flirtation, the fun…) between her characters. You can truly feel the emotion, the love, the pain.

Emily Henry doesn’t just have a high concept—she also makes it fun.

The reason I think it’s so important to be aware of this is because sometimes books and movies are not fun. Sometimes, despite it sounding so good, it falls flat. You find yourself not that into the character or the story world. You don’t really care about them. And I believe it’s because somewhere along the way, the fun factor failed to be developed. Any genre can feel fun, by the way—it’s not reserved for romances or rom-coms. Thrillers can titillate the mind as you race to find out what happens next. There might be a puzzle you’re desperately trying to solve alongside the main character (see: Gone Girl). Or take You, the book (though the show is fun, too). He’s doing horrible things, yet we can’t look away—it’s because it’s fun to be fascinated by this person entirely different from us, and yet ever so slightly relatable?

We’re mesmerized by psychopaths (at least the ones we can view safely through a screen or read in the pages of a book). They are people who think differently, act differently. My main character, Nadia, is a textbook psychopath, though like Dexter, she has a guiding mentor who has helped direct her toward only killing bad people. I love this element because it is by design fun to write—and IMO, fun to read. Someone who’s not confined by the usual boundaries of human morality… whatever will they do next? It keeps us turning the pages or watching episodes, because we really want to know.

How to Make Your Book High Concept—And Fun

The best book I’ve found about high concept—and the fun factor—is The Idea: the Seven Elements of a Viable Story for Screen, Stage, or Fiction, by Erik Bork. This book was recommended to me by

and has been an absolute game changer for me. With his 60/30/10 rule, Bork argues that 60 percent of what’s most important to a project’s chances of success is nailing the high concept pitch.Bork says a high concept pitch should have a problem that is punishing, relatable, original, believable, life-altering, entertaining, and meaningful—and goes into much more detail on each aspect (seriously, buy the book—you won’t regret it). These seven aspects all play into a pitch being high concept.

Take my pitch, for example:

An assassin disguised as a PTA president/soccer mom is given the impossible task of killing her own husband, forcing her to choose between the two most important things in her life: her job or her family.

Is it punishing? Well, yes. She’s literally forced to choose between her life with her husband and children or the job that she loves and keeps her sane (or as sane as a killer can be).

Is it relatable? Absolutely. How many moms in the world feel like they have to choose between their family or their job? Most of us, I’d argue, even while we’re trying to do both.

So on and so forth. But a game-changing moment for me was the entertaining aspect. On one hand, I wanted to smack myself in the forehead and say duh! But as an author who’s previously written psychological thrillers, I’d never thought about that factor. I suppose I assumed that if readers could relate to my main character, it would be a story they’d want to follow. And to some extent, that’s true.

But Somebody Worth Killing was a transformative book to write. It was the first time I actively thought about the experience being fun and entertaining for the reader. I worked in amusing anecdotes and bad jokes you can’t help but laugh at. I added side characters impossible not to fall in love with because of their quirks, and I made sure to poke fun at anything and everything. For the first time ever, I laughed while writing the book—and heard back from my critique partners just how fun it was!

Beyond creating a better reading experience, it was fun to write. When I tell people about the book, their eyes get wide and they almost always say, “I can’t wait to read it, when does it come out?” (the answer is June 2026 BTW 😉 )

In case you were wondering, in Bork’s 60/30/10 rule, the 30 percent “lies in structural choices, the decisions about what will happen, scene by scene…” and the final 10 percent includes the actual words the author writes—the dialogue, description, etc. That’s a lot of weight to put on the high concept!

Now, I’m not saying that your multi-generational trauma family drama has to be funny or have exciting moments (though I think the best ones have a little of that, too, because family, amirite?). I think that an immersive experience where the reader is getting what they want out of the book is its own form of entertainment, and this will look different for other genres. But I think it’s the element that I often see newer writers missing. They have their plot beats worked out, their main character arc designed, and their writing is good—but it’s just not quite coming together. And I think that, often, this is the piece that’s missing.

I also think it’s the piece that makes a good book great.

In conclusion, I will highly recommend you read Karin Gillespie’s piece for more information on high-concept pitches and try your hand at your own one—but don’t forget to work in the fun factor, to make it entertaining. It’s that piece that will take it from good to great.

Let me know in the comments: what’s the most fun you’ve had reading a book or streaming a show or a movie this summer? 🏖️

Pet Corner

Pearl has been feeling more at home every day—she’s even eating dinner with the big kitties and thinking about playing with the dogs! She also showed my printer who’s boss—apparently, printing a 320 page book for a read through was too much, so she proceeded to bap it until it stopped so she could sit on the pages.

Let me be your guide to all things reading, writing, #momlife, bad jokes, and of course, cute pets—hit subscribe, and stick around a while! I’ll see you next week with a new topic! - Jessica

I am such a fan of The Idea. Like you, when I first read it, all kinds of lightbuulbs went off. Thanks for this insightful post and for the mention.

Thank you for sharing this! I honestly had no idea fun wasn’t a thing every author thought about. I’m the complete opposite. My very first or second thought about story is the fun factor. I have to know it’s there before I can develop a plot. Also, I just ordered The Idea—thanks for the rec!